Introduction

View the video recordings for this chapter

Motivation

There is a an inspiring real story about the National Security Agency (NSA). The “Cryptologic Spectrum” is a classified internal journal regarding cryptology issued by the NSA, a US intelligence agency. The “Freedom of Information Act” (FOIA) is one of the finest examples of US legislation. According to this law, anyone may request access to official documents in general. In 2007, Michael Ravnitzky, a lawyer, requested the table of contents for each article in the NSA journal. The NSA tried to postpone his request for several years, but ultimately gave him what he requested subject to censorship on some categorised titles. He simply kept requesting the additional classified titles after getting that information!

“Tempest: A Signal Problem,” one of the significant article in the NSA journal, describes an event that took place during World War II. Significant technological advancements were made during that time, including the development of digital wireless communication. Digital signals allow people to transmit messages across the globe. The US army wanted to employ this type of communication without the opponent being able to intercept it. Thus, encryption was required to safeguard those transmissions.

The outcome of the encryption procedure is a ciphertext that can be transmitted without any hassles. Attackers are unable to decrypt the ciphertext and discover the key because of the excellent implementation of algorithm. Suppose the computer is incapable of performing the encryption during World War II without resistors oriterative circuits - what can the adversary do to find the key?

The adversary can build a machine that performs decryption; insert the ciphertext into the machine and test each keys (brute force). But, how to determine the correct key?. It is simple because the plaintext follows a logic, making the possibility of one of the following circumstances very high: an English chat, a weather report, or even an executable format - in general, Simple to check by glancing at the syntax. The key you used to decrypt the ciphertext is accurate if you receive an output that begins with “Heil Hitler”. The encryption technology at the time was not extremely sophisticated. As a result, they had to discover a technique to safeguard their ciphertexts in order to keep the secure messages safe. A one-time pad is indeed the solution to the issue.

The One-time pad, also called Vernam Cipher, is a simple and powerful encryption system. The concept behind this method is that the plain text and the key have the same length, and simply add them together for encryption - XOR is used when using digital bits, and addition is defined when using letters. The term “one-time pad” refers to a pre-shared key that can only be used once.

Why does this one-time pad protect from brute force attacks? Because plaintext ⊕ key = ciphertext* and *ciphertext ⊕ key = plaintext, meaning we can take the ciphertext and any plaintext we want, XOR them together, and get the corresponding random key. In a very secure encryption technique, like AES-256, there are 2256 possible keys and with a ciphertext which is 1MB, we have 28000000 possible keys, but if we don’t know the key there are 2256 random plaintext, and maybe just one of them is the real one. The one-time pad has been proven to be completely secure by Claude Shannon, and there is no way to break it.

Back to the years of World War II, to use one-time pad those days, they used machine which called AN/FGQ-1 mixer as can be seen in .

This machine is a kind of a box, and next to the box, was seated a wireless operator with a typewriter. The tape that came out from the typewriter was with holes that spooled into the box together with another piece of tape, which was the key. Inside the box there were little lights that lit through the holes, and little punches which would punch holes in the third piece of tape. The XOR result of the plain text and the key was the output of one operation of the machine. Then, the wireless operator fed the ciphertext into the digital radio to transmit.

Is the machine classified? If the system is designed right - you can tell the adversary whatever you want except for the secret key, and the system will remain secure.

So, these machines were used during the war, until they broke down, and at the time that happened, they have been sent to the Bell Labs (which produced the machines). The engineers who tried to repair one of the machines that sat in a room, and on the other side of the room, there was an Oscilloscope.

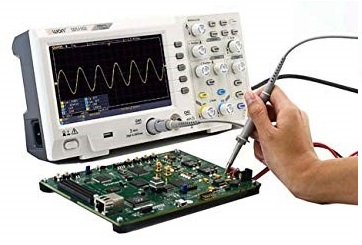

An Oscilloscope is like babies monitor - just for signals. You connect the Oscilloscope to an electric circuit, and there is a line that rising every time there is a difference in voltage. demonstrates such a setup. This Oscilloscope was not connected to the mixer, it was just laying at the other side of the room, connected to some other test equipment. The engineers discovered that every time this mixer entered the digit into the tape, they would get a pulse at the Oscilloscope. This is because that when you send a current into an electric monitor, the current is moving through the conductor and electromagnetic current is being generated. The Oscilloscope has little wires, and the electromagnetic waves can travel through those wires. As a result, we have a transmit antenna and a receive antenna, so the Oscilloscope measures the holes (the ciphertext) in the tape. Another possible explanation is that when the punches punch a hole in the tape, it consumes so much current that the voltage in the room drops a little, and then the lines in the Oscilloscope, without being connected to anything, just “jump”.

The engineers discovered that the top-secret information inside this machine was being transmitted over the air. The process the engineers were supposed to do is called responsible disclosure, meaning to report a bug. Like good engineers, they told the Secret Service people about this bug, but they did not take their diagnosis seriously. So what did they do? The Bell labs were located next to the US Secret Service office, so they set up an antenna and they listened for an hour for radio transmissions that the Secret Service got in their office, and they gave the Secret Service their “top-secrets” analyzed messages.

Obviously, the US Secret Service realized that the reported attack was not esoteric, and they asked for a solution from the engineers. The solution of Bell labs was to modify the mixers - to surround them in a wire cage which will absorb the radiation coming out from the machine, to put a shield on the machine (to make sure the power consumption is not affecting the outside), and to make sure that people are not getting close to the machine more than 30 meters. The Secret Service people decided to accept just the distance solution and not the filtering/shielding/isolation solutions, because of the high expenses and time that would cost to modify all the machines during wartime.

In 1954, the Soviet Union published a tender to build military phones. They were very specific about protecting the phones by shielding them and making sure they do not generate too much radiation. In addition, they were also publishing strict tenders for other things like engines, turbines, etc. In fact, this is an evidence that in those years, the Soviet Union actually knew about the “bug” in the machine. In conclusion, a one-time pad is the most secure cipher known, but from the story above, we can see it was broken. So, what was broken? The implementation.

Here are a couple of Modern Systems which will break using attacks on their implementation:

-

Xbox 360: Xbox is a PC that plays nothing but games, it is very cheap and you pay for the games. Attackers, obviously, want to crack the Xbox - to play games for free, to watch movies on the device or to run Linux. In Xbox there are some integrity checks, and one of the checks was done by a command called “memory compare” , so you would calculate the integrity check over whatever software it supposes to run and you would have it stored in the secure memory, and then you would try to compare using these 2 values. This command leaks the length of the number of correct bytes before the first incorrect byte, so if you compare 2 blocks and the first bit is different - the response will be fast, and if the blocks identical until the very last bit - it would take a longer. This is one of the things that was enough to break the machine.

-

Oyster Card: it is a computer without power supply and inside this computer there are stored values. Attackers could attack this card to take the train for free. There are a lot of ways to attack the implantation of that card .

-

Car Keys : Car hacking has become more commonplace in recent years, due to the increased integration with electronic systems that include the car’s own lock system. With keyless entry systems, it uses wireless or radio signals to unlock the car. These signals can in turn be intercepted and used to break into the car and even start it. One such technique is called SARA or Signal Amplification Relay Attack.

-

FPGA : a piece of hardware which is a very versatile, meaning we can find it many kinds of hardware - routers, audio equipment, spaceships, etc. the FPGA has a firmware installed inside, and if you want to copy some designs you need to find the firmware. The firmware is encrypted, but a bunch of Germans researches discovered that if you measure the power consumption of the FPGA while it is encrypting the firmware - you can find out what is the key.

When we implement an algorithm without being careful, we can be exposed to implementation attacks. To protect ourselves against those attacks, we must protect the implementation, but as we saw at World War II, this countermeasure has a price. It makes the system more expensive, and heavier.

System Implementation

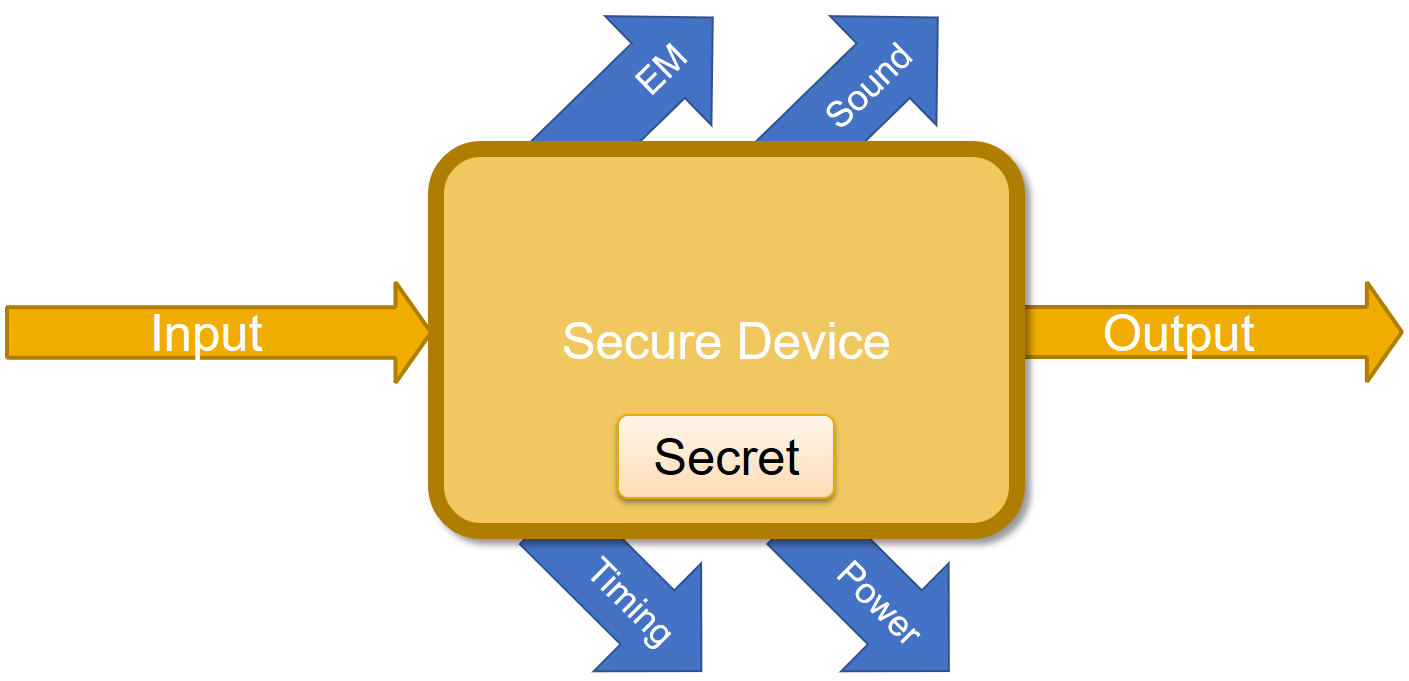

The simplest form of a computational system is a device which gets input, makes a computation and finally produces an output as can be seen in . We assume that our system contains a secret, which is not revealed to anyone before, during and after the computation process.

But, if that all what the “system” has, it is not a system, it is just an algorithm. What turns an algorithm to be a system? It is the implementation!

Think about ATM - very simple device without cryptography. The input is our credit card and a 4-digits PIN code, the output is money. If we do not know the PIN code we can go over the all possible combinations of 4-digits code (brute force), and finally find the correct PIN. Unfortunately, we have a limit of 3 trials until the card is being shredded. What an attacker can do?

As an output, and besides the money, we have also some additional outputs which have been produced by the implementation of the physical system. Those additional outputs are called “Side Channels” and they are in fact outputs that the system designer did not intend to produce. Those outputs are demonstrated in

For example, we can measure the time it takes to complete an operation, measure electromagnetic radiation, listen to the sound of the device while an operation is being completed, measure power, etc. These are Passive Attacks - meaning that we are letting the device to do its “stuff” while we are just listening.

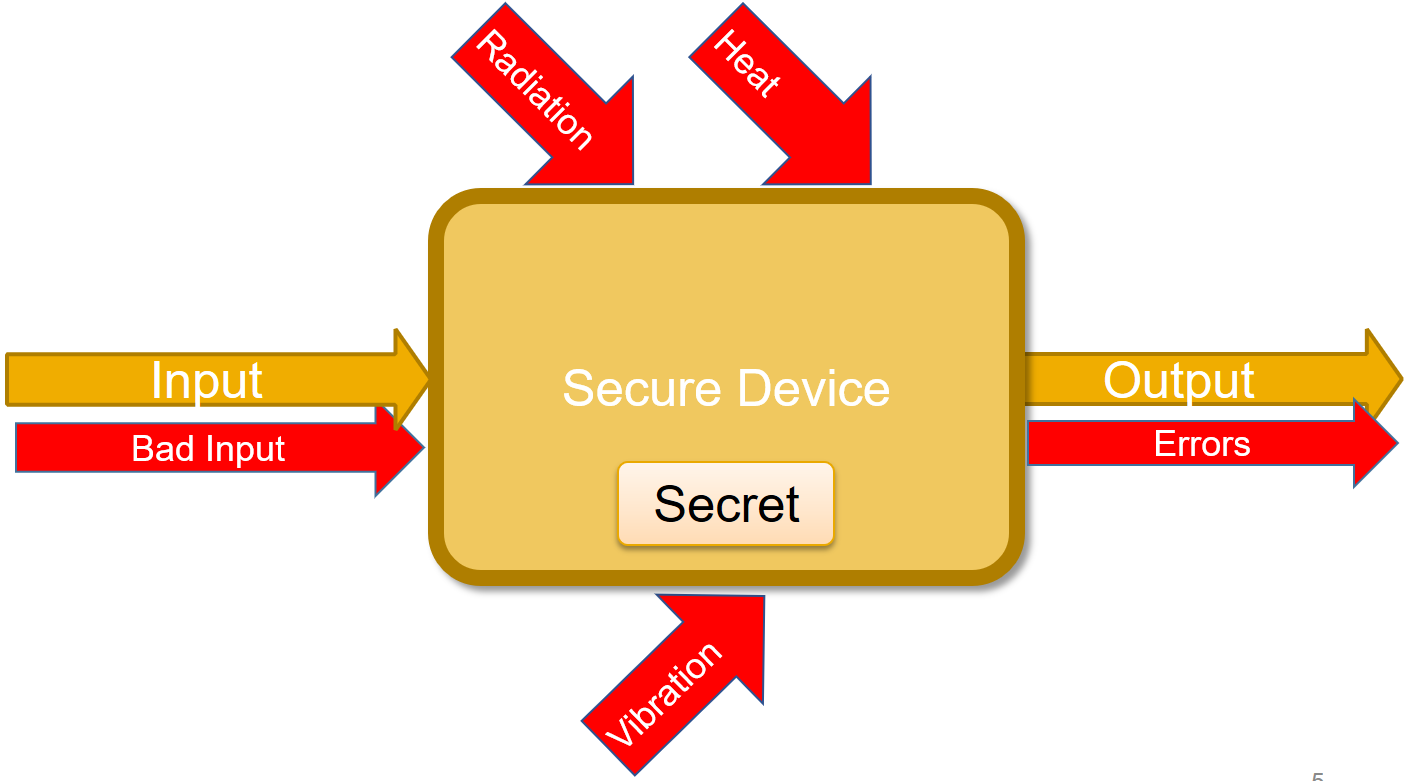

There are also Active Attacks - also called fault attacks which try to break the device under test in a way that it will be “just a little bit broken”. It can be done by turning it off in the middle of a calculation, changing its clock, etc. As a result, we might not get the actual secret, but we will get some kind of errors that can tell us a lot about the secret.

Security of a System

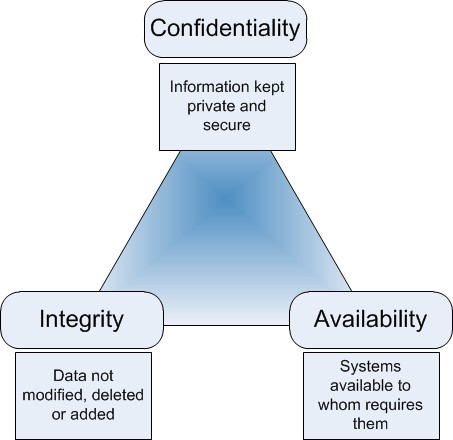

When we can say that a system is secured? Usually, we define a system as a “secured system” if the system maintains three aspects of information security, known as the CIA triad:

-

Confidentiality - when you are interacting with a system, you only get what you wanted to get. For instance, when I check my test grade, I will get my grade and not my friend’s grade. If I eavesdropped a conversation for example, it will no longer be confidential.

-

Integrity - all the data in the system is correct. A possible attack could be that one side of the communication will accept a message they are not supposed to accept. If I managed to manipulate a bank withdrawal, or jailbreak a device, its integrity would be compromised.

-

Availability - the system must work in a reasonable time. A possible attack could be a Denial of Service (DOS).

In the relation between those aspects is demonstrated as the Triangle of Information Security.

We do not have to use cryptography to secure our system. For example, if someone goes to some event without invitation, there is a security to prevent him from getting in.

An Algorithm is a process or set of rules to be followed in calculations or other problem-solving operations. An example of an algorithm is GCD/Extended GCD. An algorithm is secure when it is implementing the CIA triad mentioned above. A Protocol is when you need to get something done, for example, AES - the input is a 128-bit key and a 16-bytes plaintext (in case of different amount of bytes we can use block cipher like CBC), and the output is a ciphertext.

The millionaire problem is a classic problem by Yao and which introduce the question of whether two millionaires can learn who is richer, without revealing to one another how much money they each have. One possible solution, they could invite a poor man, tell him the secret of how much money each one has, and the poor man will announce who is richer.

Cryptographically Secure Algorithms and Protocols:

-

Encryption and Decryption - Public key-RSA, Symmetric key-AES

-

Signing and verification - must be an asymmetric key. There are 2 parties - signing party and verifying party, who gets the public key. The difference between signing and decryption is when one side sends a signed message it comes with a signature, and when one side decrypts a message it is sending only the ciphertext.

-

Key Exchange - Diffie Hellman algorithm.

-

Hashing and HMACs - a hash is a function that gets a long input (of arbitrary length) and outputs a fixed size output. A hash function is secure when it is difficult to find collisions in it, i.e 2 messages with the same hash. HMAC is a hash with a key - when you change the key, the hash is also changed.

-

Multiparty Computation - secure protocols for auctions, voting, etc.

-

Cryptocurrency - Bitcoin for example.

Secure Architectures without cryptography:

-

Secure Policies - like access control to a military base, for instance.

-

User Separation and Sandboxing - a program is divided into parts which are limited to the specific privileges they require in order to perform a specific task.

-

Virtual Memory - an application has a view of the memory, and we can take to pointer and point to some parts of the memory. We will get our old memory (which we are allowed) or the app will crash due to access to invalid memory space. In theory, we cannot get another user’s memory.

Constructing and Using a Threat Model

What is the main advantage we have as attackers which allows us to break implementations that are secure in theory? The main advantage is that we have more inputs and outputs which translates into side channels and leakage, so together it means that we can break a completely secure algorithm. But when is an algorithm’s implementation secure? CIA triad holds, but the thing that is missing here is the story, i.e. what are we allowing the attacker to do with the system? The more power we give the attacker, the less impressive the attack becomes.

Let us have a look at a little system where the assumptions were broken:

presents a wall of a bank in Ireland, on which an ATM was constructed. As we know, the ATMs are very secure systems - they have encryption, they check our ID very carefully and if we make any mistake they shred the card. What just happened, is that the ATM was stolen from the wall of a bank by thieves which took a vehicle and smashed it through the wall. They then loaded the ATM on their track, and left the vehicle to prevent the police from chasing them. We can learn from this story, that although the ATM was secure, the threat model was wrong.

The most important thing about the threat model is the story. Once we have the story, we can find out what are the different properties. We specify them as follows:

-

Victim Assets - what does the victim have that I can steal?

-

Cryptographic secretes (keys) - the keys are short, and when one key is stolen, - the attack has succeeded. There are two kinds of keys, long term, and short term.

-

Long Term Key - the private key that identifies a server. If the key is stolen, it will be possible to sign malware as a software update.

-

Short Term Key - a key that is generated during a session and is initialized from the long-term key. If this key gets stolen it is possible to decode all the messages in the current session and modify/inject them.

Notice that if the long-term key is stolen, it does not mean the short-term key is stolen.

-

-

State secrets - for example, ASLR or configuration of a system. If someone can find out the addresses of functions in the memory of a victim, he can write exploits.

-

Human secrets - things which the users do not want to reveal like passwords, medical condition, etc.

-

-

Attacker Capabilities - what can the attacker do?

-

Off-path - the attacker is sitting somewhere in the world - cannot observe or communicate with you, but he can attack you somehow.

-

Passive Man in the Middle - attacker who can see the victim communication with the server, but cannot communicate with the victim directly.

-

Active Man in the Middle - an attacker who can interact with the server and can do replay attacks.

-

Physical Access - an attacker who has physical access to the victim. For example, removing or unplugging or melting stuff in the system.

An important thing we need to consider when we are talking about attacker capabilities is the other defenses we must protect our system with, like guards or cameras. Another thing is the scale of the attack, meaning how many systems we can attack at once. If the attack is physical, it is probably just one system. If the attacker attacks from an android application, he might attack all the phones in the world.

-

-

Attacker Objectives - who are the attackers? What do they want?

-

Stealing stuff - the attacker might want to steal your secrets.

-

Duplicating stuff - for example, the attacker can buy one smart TV card, and generate a thousand duplicates from this card to sell them.

-

Forging stuff - the attacker creates something new, driver licenses for instance.

-

Corrupting stuff - the attacker breaks something and decommissioned the system.

-

Of course, the more limits we put on the attacker, the more and more impressive the attack becomes.

Related Work

The whole topic of Attacks on implementation has been widely researched, and side channels attacks have been found on many various types of implantation. Here are a few interesting such types of side channels attacks and examples for actual attacks on those topics:

-

Audio-based attacks - for example, ultrasonic beacons and acoustic cryptanalysis. a type of side-channel attack that exploits sounds emitted by computers or other devices. Most of the modern acoustic audio-based attacks focus on the sounds produced by computer keyboards and internal computer components, but historically it has also been applied to impact printers and electromechanical deciphering machines. here are a few examples of real-life acoustic attacks:

-

1 In 2004, Dmitri Asonov and Rakesh Agrawal of the IBM Almaden Research Center announced that computer keyboards and keypads used on telephones and automated teller machines (ATMs) are vulnerable to attacks based on the sounds produced by different keys. Their attack employed a neural network to recognize the key being pressed. By analyzing recorded sounds, they were able to recover the text of data being entered. These techniques allow an attacker using covert listening devices to obtain passwords, passphrases, personal identification numbers (PINs), and other information entered via keyboards. In 2005, a group of UC Berkeley researchers performed a number of practical experiments demonstrating the validity of this kind of threat.

-

2 A new technique discovered by a research team at Israel’s Ben-Gurion University Cybersecurity Research Center allows data to be extracted using a computer’s speakers and headphones. Forbes published a report stating that researchers found a way to see information being displayed, by using a microphone, with 96.5 percent accuracy.

-

-

Differential fault analysis those attacks take multiple traces of two sets of data, then computes the difference of the average of these traces. If the difference is close to zero, then the two sets are not correlated, and if the p-value (typically ≥ 0.05) is higher, correlation can be assumed to be possible. An example of an attack that was achieved by this is cracking the difficult-to-solve 128-bit AES. Using differential fault analysis it was shown that the key can be broken into 16 bytes, where each byte can be solved individually. Testing each byte requires only 28, or 256 attempts, which means it would only take 16 x 256 or 4,096 attempts to be able to decipher the entire encryption key.

-

Data remanence Data remanence is the residual representation of digital data that remains even after attempts have been made to remove or erase the data. This residue may result from data being left intact by a nominal file deletion operation, by reformatting of storage media that does not remove data previously written to the media, or through physical properties of the storage media that allow previously written data to be recovered. Data remanence may make inadvertent disclosure of sensitive information possible should the storage media be released into an uncontrolled environment (e.g., thrown in the trash or lost) an example of an attack that is using data romance is cold boots which steal sensitive cryptographic materials like cryptographic keys by Keeping DRAMs at lower room temperature, say -50 degrees C, and making it hard for the Dram to preserve his data properly. more details on this attack can be found here cold-boot-attack.

-

Optical attacks these attacks range from the relatively simple (eavesdropping on a monitor via reflections) through to complex (communicating with an infected device via LED blinks). An article of optical attack utilizing the photonic side-channel against a public-key of common implementations of RSA optical side-channel against a public-key of RSA.

In addition to those attacks, there are even more side channels attacks research and new weaknesses are discovered every time. More of such attacks like Specter, RowHummer, and many more will be described widely in this course.

Research Highlights

The paper discusses the meaning and implications of confining a problem during its execution. Multiple examples are presented to describe the problem and necessary conditions are stated and justified.

We are already familiar with the need of protection systems to safeguard the data from unauthorized access or modification and programs from unauthorized execution. This requires creating a controlled environment where another, perhaps untrustworthy program could be run safely and was solved prior.

Terminology - The customer wants to ensure that the service cannot read or modify any data which he did not explicitly grant access to.

Even after we prevented all unauthorized access the service may be still able to injure the customer, this can be achieved by leaking the input data that the customer gives it. The service might leak data which the customer regards as confidential and generally there will be no indication that the security of data has been compromised. From now, the problem of constraining a service will be called the confinement problem. We would like to characterize this problem precisely and describe methods to block some of the possible escape paths for data from confinement.

Our main goal is to confine an arbitrary program. The program may not be able to work as usual when it is under confinement, but it will be unable to leak data.

Some of the possible leaks might be (1) collecting data and returning it to the owner when called, (2) writing to a permanent file in its owner’s directory, (3) creating a temporary file for the owner to read before the service to complete its work, (4) Using the system’s interprocess communication facility. After presenting these types of leaks, the paper continues to elaborate about more advanced leaks through covert channels, i.e. channels which are not intended for information transfer.

The first method is done by exploiting interlocks which prevent files from being open for writing and reading at the same time. The service and its owner can use this to simulate a shared Boolean variable which one program can set and the other can read, for transmitting a single bit. The second method is created by varying the ratio of computing to input/output or paging rate. A concurrently running process can observe the performance of the system and receive this information.

The channels described above fall into three categories: storage of various kinds, Legitimate communication channels and covert channels.

The paper then continues to discuss rules for confinement. The first observation is that a confined program must be memoryless. We can now state a rule of total isolation, forcing a confined program to not make any calls to any other programs. However, this rule is impractical. We need to improve this situation. A new confinement rule that we can formulate is transitivity, meaning that if a confined program calls another untrusted program, the called program must also be confined.

Then, two simple principles are presented. The first one is called masking. This rule states that a confined program must allow the caller to determine its input into the different channels. However, in the case of covert channels, one further point must be made. We need to ensure that the input of a confined program to covert channels conforms to the caller’s specifications. This might require slowing the program down, generating spurious disk references etc.